GRITTY, NEVER QUIT, TEAM-ORIENTED CULTURES MATTER in SPORTS AND LIFE.

Concerned about dealing with your players parents?

Need advice on enhancing your players game-day performance?

Want to know how to run an effective practice?

Finally, a concise guide to help the youth sports coach succeed with players and parents!

This is the perfect book for coaches, players,

and parents across all youth sports.

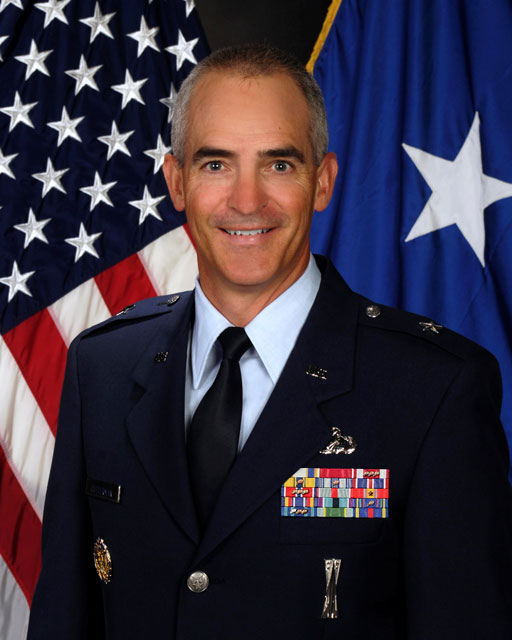

Retired Air Force Brigadier General Greg Gutterman

captured 3-decades of hockey coaching experience into 7 practical recommendations for coaches.

From training to game-day management to

communicating with parents, this is your definitive blueprint for becoming an effective player-centric coach.

You can do this coach, and this book will show you the way!

If you lead, teach, or coach at any level,

this is the perfect book for you!

ASK COACH GUTT

“This is a must-read for any current or aspiring coach. In “Hustle and Have Fun!” General Gutterman has captured a great insight: character and values are essential for success in all aspects of your life. This book is really something special, Bravo!”

Coach Gutt’s Recommendations Include

Treat Parents Like Adults

Even if they are acting like children

Manage Expectations

A picture is worth 1,000 words

Chapter 1

I made the top-tier “A” team from ages 8 to 12 growing up playing hockey in Minnesota. In my fifth season I was cut to the “B” team at tryouts. A quick scan of the before and after rosters highlighted the fact I was the only player demoted that year. All of my good friends and teammates remained on the “A” team ahead of me.

I was hurt, embarrassed, and wondered how I could keep playing. Somehow in my 13-year-old shocked state, I gathered the moral courage to ask the coach why I didn’t make the top team.

“Gutt, you have the skill and speed. But you are not ready for the physical side of the game yet at this level. You will get more playing time and develop more as a player on the B-team. I’m confident this will make you a better overall player” the coach said.

My parents talked to the coach too, and they heard the same reasoning with one addition. The coach told my parents, “Greg can be a great player someday if he wants to do the work it requires to become one. This is something he can do on his own, irrespective of if he is playing on the A or the B team.” When my dad finished telling me what the coach had said, he finished by saying “If you want to make the A team next year, it’s there for the taking. You can use this experience to fuel your fire, or to quit. That choice is yours.”

The downgrade pushed me to put in more effort on and off the ice. I was 100 percent committed and motivated to earn my way back onto the “A” team the following season. As a B-teamer I became the leading scorer and biggest threat to every opponent we faced.

In practices I worked to be the fastest in every drill no matter how tired I was, and I went to as many of the A-team games as I could to support my friends. When the season ended, I was proud of the fact I followed my dad’s advice and used the disappointment to fuel my desire for focused improvement.

Before I knew it my B-team season had ended and the Minnesota snow was giving way to Spring. Day by day I walked to and from school watching the ice slowly melt on my beloved outdoor rink. It first became slush, then a shallow pond, and finally a 17,000-square-foot puddle of mud. That’s when I noticed that sunk deep into the mud were two, four by-six-foot steel fenced abandoned hockey nets. I called a friend, and within an hour one of the rusted hockey nets was in my parent’s single-car garage, mud and all!

All spring and summer long my friend and I shot pucks. Hundreds of shots became thousands. We invented new games to introduce competition and keep the time in the garage fun and interesting. First to hit the four corners and fastest to snipe thirty shots became my favorite games. My friend enjoyed goalie war using tennis balls because he won that game every time (turns out I am a terrible goalie). At my mom’s insistence we even learned how hard it was to repair the holes and dents in the garage walls that resulted from our wayward shots. After which, we focused harder on hitting the net, and just to be safe, we staple-gunned old sheets and blankets from the garage rafters to stop our inaccurate snipes from doing further damage.

By the next season, I was a different player. Faster, stronger, more skilled, and significantly tougher mentally. I gained more confidence and captured a much better work ethic. As a result, I made the A team’s first line at age 14 and every season thereafter.

My player-centric coach was 100 percent correct: I developed more as a B-team player than I ever would have as an A-team player. Thank you coach for giving me the nudge I needed to take personal responsibility and start working to become my very best!

The lesson I learned all those years ago is now a frequently repeated phrase I tell my players. The small efforts toward improvement, consistently applied day in and day out, will reap tremendous lifetime rewards. The muddy and rusted hockey net in my garage was my daily reminder to bring my personal best effort, both physically and mentally, to every undertaking. I have found as a coach that there is no higher sense of satisfaction than watching a student-athlete go from “I can’t” to “I can’t yet” to “I can” and ultimately, “I did.” The players will carry this process and mindset of continual improvement and selfbelief with them throughout their entire lives. This helps create people of character, and it is why coaching is such an instrumental voluntary profession.

Each February I hold a Senior Banquet for my graduating high-school hockey players. I think it is important for the coaches to recognize and honor the players who helped make the program better than they found it. The players who built and sustain a culture of excellence where doing your ultimate best is the measure of success, not a scoreboard.

I remind the Seniors several times before the banquet they will be required to give a short speech after the dinner. I also tell them, “If you only say one thing, make sure it is to thank your Mom and Dad.”

Being grateful for all the time, energy, and money your parents have sacrificed so you can play the sport is important. In my opinion, gratitude and humility are at the top of the list of admirable qualities in any human being.

Public speaking is also an essential life skill and our tradition helps (or in some cases forces) a few of our seniors to get out of their shells a little. The primary objective of the speeches, however, is for our Seniors to let their teammates know what playing for this team has meant to them. Every year this event

gets more and more emotional for me.

A few seasons ago, as my son was giving his senior speech, I caught tears welling up in my eyes but I held them back. A few seasons later the tear ducts let loose during one of our senior’s speeches.

He started his talk with “I’m not gonna cry,” and within a few minutes, the entire room was in some form of a hand-to-cheek wiping motion. In this Senior’s final speech, and during his short time to talk, he first thanked his parents. Then he shared a few funny stories before looking at one of his life-long teammates, our senior goalie. As they exchanged eye contact, he thanked him for being such a good teammate, a friend, a brother.

Then he looked at his fifteen other teammates and told them how much he loved them. Yes, a High School Senior used the word love. As he talked, he started to pause in between words to let the tears slowly drop from his eyes and to recapture enough composure to keep talking.

He finished by thanking the coaches. With tears free-falling from his eyes, we heard, “I have never been on a team where the coaches believed in me so much. Never.” Then he turned toward where I was sitting, and asked, “Can I get a hug, coach?” I am tearing up just thinking about this story, still humbled and honored by the validation this provided me as his coach.

I wanted to share these two particular stories with you to highlight a stark contrast. On one hand my youth coach had to cut me to the “B” team to inspire my improvement and teach me a valuable life lesson on giving your personal best efforts in all you do. On the other hand, my senior needed to know his coach believed in him, so he could in turn learn the importance of believing in himself. Both stories have the same main point: a player-centric coach puts what is in the best interest of the player’s long-term growth and development above all else. This, not a single game, season, or scoreboard, is what being a

player-centric coach is all about.

Chapters

Pages

A portion of the proceeds from this book will be

donated to the not-for-profit Academy Hockey Club

(academyhockey.org). The Academy’s mission is to

increase participation and diversity in the sport of ice

hockey. The Academy accomplishes its mission by

providing free learn-to-skate and learn-to-play

opportunities for young athletes. Thank you for

supporting the Academy by purchasing this book.

General.

COACH.

author.

What happens when hockey takes you to a scholarship and a career? A Minnesota kid does OK for himself.

From the AF Academy to the halls of the Pentagon, ending with a star, and a posting in Dayton Ohio where his wife hails, Greg Gutterman never lost touch with hockey. It ran through his life like a guiding north star.

Coaching his own boys, after coaching at all other amateur levels, he decided to found the Academy Hockey Club which provides kids up to 8 with free equipment, ice time and coaching to allow them to experience the sport he loves.

This book is here to help him share his love of the game and to give back.

Greg Gutterman

GUTT CHECK™ FOR YOUTH COACHES

Consulting

Workshops

SIGN UP FOR A GUTT CHECK NEWSLETTER

Your email won’t be shared with anyone else. We promise.

For the latest tips on this thing we love called coaching.